How to Write a Motion to Dismiss: A Practical Guide for Early Wins

Writing a motion to dismiss is about spotting a fatal, incurable flaw in the plaintiff's complaint. You’re not arguing the facts yet; you're demonstrating that even if every single allegation the plaintiff makes is true, they still don’t have a legal leg to stand on. A successful motion can end the fight before it really begins, saving your client a mountain of time, stress, and legal fees.

Building Your Strategic Foundation Before You Write

Before you ever start drafting, you need to think strategically. A motion to dismiss isn’t just a document; it’s a calculated move designed to dismantle the plaintiff’s case from the ground up. This is your chance to show the court that the lawsuit is fundamentally broken.

This pre-drafting phase is where the real work happens. It’s about shifting from a defensive posture to proactively controlling where the case is headed. If you rush this part, you'll end up with generic arguments that judges have seen—and swatted down—a thousand times before.

Pinpoint Your Strongest Grounds for Dismissal

Your first move is to dissect the complaint, looking for those critical weaknesses. You're not trying to win a factual dispute at this stage. Instead, your job is to prove that the facts, as pleaded, simply don't add up to a valid legal claim.

Before you go all-in on a Rule 12(b)(6) motion, make sure you've covered your procedural bases. These often provide a cleaner, more definitive path to dismissal.

Here’s a quick-reference table outlining some of the most common grounds you'll encounter.

Common Grounds for Filing a Motion to Dismiss

| Grounds for Dismissal (FRCP Rule) | Brief Description | Strategic Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 12(b)(1) Lack of Subject-Matter Jurisdiction | The court lacks the constitutional or statutory authority to hear the case (e.g., no federal question, no diversity). | This is a powerhouse argument. It can be raised at any time, and if successful, the court must dismiss the case. |

| 12(b)(2) Lack of Personal Jurisdiction | The court doesn't have legal power over the defendant, typically due to insufficient contacts with the forum state. | Crucial for out-of-state defendants. Winning here often means the plaintiff has to start over in a different court. |

| 12(b)(3) Improper Venue | The plaintiff filed the lawsuit in the wrong geographical district. | Can result in dismissal or transfer to the proper court. It’s less final than a jurisdictional dismissal but still a key procedural check. |

| 12(b)(6) Failure to State a Claim | Even if all the plaintiff's factual allegations are true, they don't constitute a recognized legal cause of action. | The most common but often the toughest to win. The court must accept the complaint's facts as true and draw all inferences in the plaintiff's favor. |

Winning on these grounds requires precision. A great example is a recent case where an employee alleged religious discrimination after being denied a vaccine exemption. The company’s motion argued her objections were philosophical, not religious. The motion failed because she had quoted scripture and connected it to her beliefs, making the claim plausible enough to survive dismissal. The takeaway? You must attack the legal framework, not just what you perceive as a weak factual premise.

A motion to dismiss forces the court to ask a simple question: "Assuming everything the plaintiff says is true, do they still have a case?" Your job is to frame the answer as a definitive "no."

Verify Deadlines and Local Rules

Don't let a simple procedural misstep sink your brilliant legal argument. The first thing you absolutely must do is calendar the deadline to respond to the complaint. Missing it is one of the easiest ways to find yourself facing a default judgment.

Next, you need to become an expert on the local rules of the court and, just as importantly, the individual practices of your assigned judge. These rules can dictate everything from:

- Page limits and specific formatting requirements (font, margins, line spacing).

- Whether you're required to meet and confer with opposing counsel before filing.

- The required citation format for legal authorities.

- Mandates for submitting a proposed order along with your motion.

Ignoring these details is a red flag to the court that you're careless. It can get your motion kicked back on a technicality before a judge ever reads your argument. This meticulous groundwork is the foundation of good lawyering. As you get a better handle on what is case management in law, you'll see that mastering these small but critical details is what separates the pros from the amateurs.

Anatomy of a Winning Motion to Dismiss

A truly effective motion to dismiss isn’t just a document; it's a scalpel. It’s your first and best chance to surgically dismantle the plaintiff’s case, exposing its fatal flaws before the expense and hassle of discovery even begins. Getting this structure right is the key to drafting a motion that a judge will actually grant.

Think of it as building a logical, persuasive argument from the ground up. Each piece has a specific job to do, and they all have to work together seamlessly.

First Impressions: The Caption and Introduction

The very top of the page is your first handshake with the judge. The caption is simple but crucial—it needs to clearly name the parties, the court, and the case number. A clean, perfectly formatted caption signals that you're a professional who pays attention to detail. Don't gloss over it.

Your introduction is your elevator pitch. You have about two or three sentences to tell the court exactly what's going on. It needs to hit three key points, and fast:

- Who you are: "Defendant ABC Corporation..."

- Why you're here: "...moves to dismiss the Complaint pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6)..."

- What you want: "...and respectfully requests the Court dismiss all claims with prejudice."

This is not the place for winding arguments or flowery prose. It's a direct, powerful summary that frames the entire motion. The judge should know what you want and the rule you're relying on before they even finish the first paragraph.

Weaving the Narrative: The Statement of Facts

Now for the tricky part: the Statement of Facts. This section is a masterclass in subtlety. Your only job here is to tell the story using only the facts alleged in the plaintiff's complaint. This is a hard-and-fast rule. You absolutely cannot bring in new evidence or dispute their allegations.

For the purpose of the motion, you have to treat every allegation as true. Your goal is to arrange those "true" facts in a way that telegraphs the legal weakness of their case. You're telling their story, but through a lens that highlights the gaps and inconsistencies. Think of yourself as a narrator guiding the reader to an inevitable conclusion—that even if everything the plaintiff says is true, they still lose.

The Knockout Punch: Your Legal Argument

This is where you land the blows. The legal argument section is the core of your motion, where you connect the plaintiff's own facts to the law and show the judge precisely why the case must be thrown out.

You always lead with the legal standard. In federal court, that means kicking things off with the "plausibility" standard from the landmark Supreme Court cases Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly and Ashcroft v. Iqbal. These cases changed the game, requiring a complaint to allege enough facts to make a claim "plausible on its face," not just theoretically possible.

The Iqbal decision was a seismic shift in litigation. Plaintiffs can no longer get by with "naked assertions devoid of further factual enhancement." Your argument needs to show the court exactly how the complaint is full of conclusory statements rather than plausible facts.

Once you’ve set the standard, you attack each of the plaintiff's claims one by one in their own distinct sub-sections. This makes your argument incredibly easy for a busy judge to read and digest. For each count, follow this pattern:

- Briefly identify the claim you're addressing (e.g., "Count I - Breach of Contract").

- State the required legal elements for that claim in your jurisdiction.

- Show how the facts alleged in the complaint fail to satisfy one or more of those elements.

- Drive the point home with citations to controlling case law.

Your command of legal research methods is non-negotiable here. Finding cases where courts in your jurisdiction dismissed similar claims is what gives your motion its power.

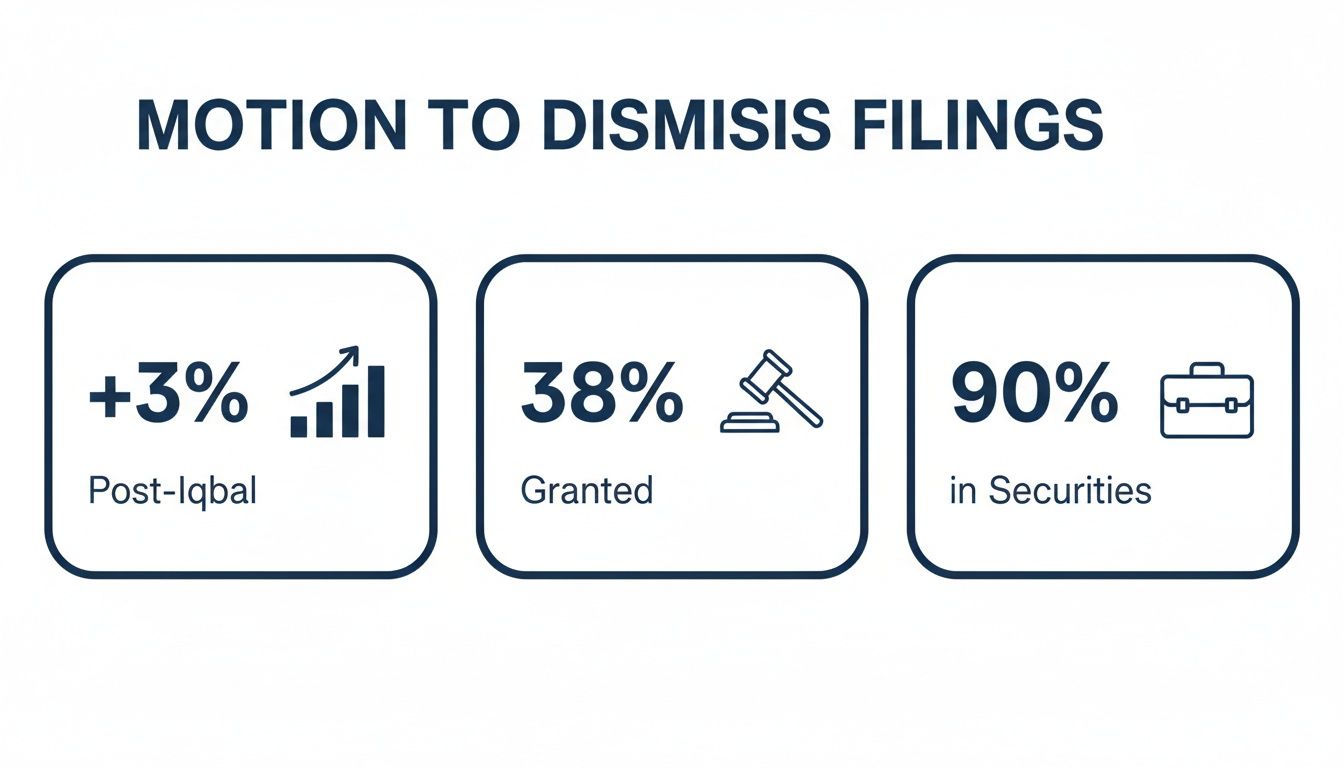

The strategic value of these motions has skyrocketed. After the Iqbal ruling made it harder for plaintiffs to survive dismissal, the filing rate in federal court jumped from 34% to 37% of all cases. Monthly filings shot up from an average of 6,180 to 7,340. In hot-button areas like securities class actions, they’re filed in over 90% of cases and succeed almost 50% of the time, proving they are a cornerstone of modern defense strategy.

Sticking the Landing: The Conclusion and Prayer for Relief

You're almost there. Your conclusion should be short, sharp, and confident. Don't re-argue your entire motion. Just sum it up in a sentence or two, reminding the court that the plaintiff has failed to state a valid claim and dismissal is the only proper outcome.

The very last piece is the Prayer for Relief. This is the formal "ask" that mirrors your introduction. You'll explicitly request that the court grant the motion and dismiss the complaint. Make sure you specify whether you want the dismissal to be with prejudice (meaning the plaintiff can't refile the claim) or without prejudice (they get another chance to amend). You should almost always be fighting for a dismissal with prejudice. That's how you win.

Building Your Killer Legal Argument

This is where the rubber meets the road. Your legal argument is the core of the motion, the part where all your prep work—the research, the rule-checking, the strategic thinking—comes together to systematically take apart the plaintiff's case. A winning argument isn't about dramatic flair; it’s a precise, logical dismantling of the complaint, built squarely on the correct legal standard.

You're essentially showing the judge, point by point, why the case can't move forward. Every point you make needs to be anchored to controlling case law, and every attack on the complaint has to be surgical. The goal is to make the judge feel that granting your motion is not just the right call, but the only possible one.

The Twombly/Iqbal Plausibility Standard is Your Best Friend

The entire landscape of dismissal motions changed after two crucial Supreme Court cases: Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly and Ashcroft v. Iqbal. These cases gave us the “plausibility” standard, which is now your primary weapon. It demands that a complaint do more than just make accusations; it has to state a claim for relief that is "plausible on its face."

What does that mean in practice? It means a plaintiff can no longer get by with conclusory statements, legal buzzwords, or what the Court called "naked assertions." You have to comb through the complaint and pinpoint every instance where the plaintiff makes a logical jump without laying the factual groundwork to support it.

A classic example is a complaint that just says the defendant "entered into a conspiracy" but offers no facts about who was involved, when it happened, or what they allegedly agreed to do. That’s a textbook conclusory statement that’s ripe for a dismissal under Iqbal.

Take the Complaint Down, Claim by Claim

Don't throw everything at the wall and see what sticks. A messy, disorganized argument will only confuse and annoy the judge. The best way to structure your argument is to attack each of the plaintiff's claims in separate, clearly labeled subsections. It makes your motion incredibly easy to follow and shows you've done a thorough, professional job.

For each claim, I stick to a simple, effective formula:

- Identify the claim you're targeting. (e.g., "Count I: Breach of Contract Fails to State a Claim")

- Lay out the essential legal elements for that specific claim in your jurisdiction.

- Show exactly how the facts alleged in the complaint fail to meet one or more of those elements.

- Back it all up with citations to binding precedent, ideally from cases with similar facts.

This method isn’t just about saying a claim is weak; it demonstrates its legal impossibility based on the plaintiff's own words.

The numbers show just how powerful a well-argued motion can be, especially after the Iqbal decision.

With nearly 40% of motions being granted, it's clear that a strong argument can stop a lawsuit in its tracks, saving clients a fortune in discovery costs.

Use Case Law to Tell a Story

Good legal writing does more than just cite cases. Great legal writing uses precedent to weave a narrative that guides the judge to your conclusion. Don't just drop a case name and a citation; explain why it matters and how the facts in that precedent line up with the fatal flaws in the plaintiff's complaint.

And what about a case that seems to go against you? Never, ever ignore it. Tackle it head-on. Distinguish it by explaining precisely why the facts, law, or procedural posture of that case make it inapplicable here. Addressing bad precedent shows the court you're credible and have done your homework. These narrative techniques are crucial in any legal document, and we cover them in more detail in our guide on how to draft a legal brief.

Go for the Knockout: Dismissal "With Prejudice"

Finally, your argument needs to be explicit about what you want. A dismissal "without prejudice" is only a temporary victory; it's an invitation for the plaintiff to fix their complaint and try again. The real goal is a dismissal "with prejudice," which is a final judgment that slams the door on the case for good.

A dismissal "without prejudice" is just a speed bump for the plaintiff. Arguing for a dismissal "with prejudice" is how you win the race for your client.

To get there, you have to convince the court that the complaint's defects are incurable. For instance, if the claim is obviously barred by the statute of limitations, no amount of rewriting can fix that. You must clearly argue why any amendment would be futile, giving the judge the legal justification needed to end the litigation permanently.

Speed Up Your Drafting with Whisperit

Let’s be honest, high-stakes legal writing is a grind. Drafting a motion to dismiss from scratch means you're constantly juggling research, the case file, and a mountain of formatting rules. It can burn through hours you don't have. The real goal isn't just about writing faster; it's about producing a stronger, more persuasive document with less friction.

This is where a tool like Whisperit really shines. It's not about replacing your legal expertise but amplifying it. Think of it as a way to work smarter, not harder, so you can get a polished, court-ready motion out the door in a fraction of the time. Let's look at how you can put its features to practical use.

This kind of setup, integrating voice and AI, is a game-changer for the old-school drafting grind. By letting you dictate your thoughts while an AI handles the structure, you can finally focus completely on the substance of your argument instead of the mechanics of typing and formatting.

Get Your Thoughts Down Instantly with Transcription

Some of the best legal arguments start as a quick-fire train of thought—connecting case law, spotting weaknesses in the complaint, and mapping out the logic. The problem? Typing is slow, and it can break that creative flow. Whisperit’s real-time transcription lets you dictate those initial thoughts directly into the editor, capturing every complex idea as fast as you can say it.

Imagine you're tearing apart a flimsy complaint. Instead of stopping to type out every point, you can just talk it through: "Okay, the plaintiff’s breach of contract claim is dead on arrival—it fails to allege consideration. Paragraph 14 is just a conclusory statement with zero factual basis for a binding agreement..." This keeps your mind locked on legal strategy. Exploring the best dictation software for writers can also give you an edge, letting you verbalize complex arguments directly into text.

Build Your Motion on a Solid Foundation

Staring at a blank page is the most inefficient way to start a motion. It's also a great way to make a mistake, like forgetting a required section or using outdated boilerplate. Whisperit’s Drafting Templates solve this by generating a perfectly structured motion in one click.

These aren't just generic outlines. You can build and save custom templates specifically for your firm that include:

- Proper Headings: The Caption, Introduction, Statement of Facts, Legal Argument, Conclusion, and Prayer for Relief are all there, right from the start.

- Essential Boilerplate: That standard Twombly/Iqbal plausibility language? It's inserted automatically, saving you from hunting it down every time.

- Jurisdictional Nuances: Keep separate templates for state and federal court, each pre-loaded with the right formatting and rule citations.

This simple step ensures every motion is consistent and compliant from the get-go, letting you jump straight into the meat of your arguments.

A well-structured template is more than a time-saver; it’s a quality control mechanism. It eliminates the cognitive load of remembering formatting rules and lets you focus 100% of your brainpower on crafting a winning argument.

Keep Everything Consistent with Style Profiles

Every firm has its own style guide, whether it's written down or just understood. Manually enforcing those rules for citations, tone, and formatting across a 20-page motion is tedious and a recipe for inconsistency. Whisperit's Style Profiles automate this entire cleanup process.

After you've dictated or typed your argument, just apply your firm's pre-configured Style Profile. It acts like a final proofread, instantly cleaning up your document to meet firm standards. For example, it can:

- Standardize all case law citations to Bluebook or another preferred format.

- Ensure a consistent, formal tone across the entire motion.

- Apply the correct numbering and indentation for all the subsections in your argument.

This is a huge advantage for producing professional, uniform work without spending hours on manual review. For a closer look at these features, our Whisperit feature guide breaks down exactly how to get the most out of the platform.

Finally, the AI Navigator keeps your key documents right where you need them. If you’re drafting the argument section and need to reference a specific allegation, you can just ask, "Pull up paragraph 27 of the complaint." You get the information you need without ever leaving your draft. This eliminates the constant back-and-forth between windows, keeping your momentum strong and helping you build a more precise and compelling motion.

Sidestepping Common Traps in Your Motion

Even seasoned litigators can fall into a few common traps when drafting a motion to dismiss. A single, seemingly minor error can torpedo an otherwise brilliant legal argument, giving the court an easy reason to deny your motion. Knowing what these pitfalls are is the best way to steer clear of them.

Resisting the Urge to Argue the Facts

This is the big one. It's the most frequent and fatal mistake I see. A motion to dismiss is not your chance to tell your side of the story or dispute what the plaintiff claims happened. At this stage, you’re stuck within the “four corners” of the complaint. That means you have to treat every factual allegation as if it’s true.

If you start bringing in outside evidence—say, an affidavit from your client or a document the plaintiff never mentioned—you risk having the court convert your motion into one for summary judgment. That’s a completely different battle with a much tougher standard, and it’s a strategic decision you want to make on your own terms, not one you want forced on you.

Ignoring Local Rules and the Judge’s Quirks

Another critical misstep is glossing over the local court rules or, just as important, the specific preferences of your assigned judge. These aren't just suggestions; they're rules of the road. Ignoring them can get your motion bounced before the judge even gets to your argument.

Many courts have strict page limits, very specific formatting rules (down to the font and margin size), or even a requirement that you “meet and confer” with the other side before you can even file. Blowing these off sends a bad signal. It tells the court you’re either sloppy or you don't respect their process, and neither impression does you any favors.

A motion to dismiss is as much about procedural precision as it is about legal brilliance. Getting the small things right builds credibility and shows the court you’re a pro.

Fumbling the Legal Standard

Simply quoting the Twombly/Iqbal plausibility standard is table stakes. Where lawyers often go wrong is in the application. Your goal isn't just to announce that the complaint is conclusory; it's to demonstrate why. You have to connect the dots for the judge.

Instead of just saying, "The complaint fails to allege a plausible claim," you need to get specific. Pinpoint the exact allegations and explain why they are nothing more than "naked assertions devoid of further factual enhancement."

- Weak: "Plaintiff's conspiracy claim is conclusory."

- Strong: "Plaintiff alleges a 'conspiracy' in Paragraph 15 but offers no facts about who conspired, when the agreement was made, or what the agreement’s purpose was. This fails to nudge the claim across the line from conceivable to plausible."

That level of detailed analysis is what wins motions. If you want to sharpen this skill, our guide on essential legal writing tips is a great resource for making your arguments land with more impact.

Knowing When an Exhibit Is Your Friend

While you generally have to avoid new evidence, there’s a crucial exception to the rule. If the plaintiff's entire case hinges on a document they conveniently forgot to attach to their complaint—like a contract—you can often attach it yourself. This works if the document is central to their claim and its authenticity is not in dispute.

This can be a game-changing tactic. If a plaintiff brings a breach of contract claim but completely misrepresents what the contract actually says, attaching the real thing can blow their case out of the water. It gives the court a clear and undeniable reason to grant your motion. Just be careful—this move is only for when the document itself is undisputed.

FAQs: Navigating the Nuances of Motions to Dismiss

Even with a solid drafting process, a few key questions always seem to pop up. Here are some quick, practical answers to the most common queries I hear about dismissal motions.

Motion to Dismiss vs. Motion for Summary Judgment

It's easy to mix these up, but they serve completely different purposes and come at very different stages of litigation.

A motion to dismiss is a pre-discovery tool. You're essentially telling the court, "Your Honor, even if we assume every single fact the plaintiff alleged is true, they still haven't stated a valid legal claim." The focus is entirely on the legal sufficiency of the complaint itself.

A motion for summary judgment, however, is filed after discovery has happened. Here, you're arguing that the facts are no longer in dispute. Based on the evidence gathered—depositions, documents, affidavits—you're telling the court there's no genuine issue left for a jury to decide, so you should win as a matter of law.

Can I Attach Exhibits to My Motion?

The short answer is: probably not, and you should be careful. A motion to dismiss is almost always decided based on the "four corners" of the complaint. The court only looks at what the plaintiff pleaded.

But there's a critical exception. Let's say the plaintiff sues for breach of contract but conveniently "forgets" to attach the actual contract. If that contract is central to their claim, you can often attach it. This can be a game-changer.

Attaching a central, undisputed document that the plaintiff omitted can be a powerful move. If the contract's actual text flatly contradicts the plaintiff's allegations, it provides the court with a clear, direct path to dismissal.

Just be aware that introducing outside evidence can sometimes trigger a conversion, turning your motion to dismiss into a motion for summary judgment, which is a different beast entirely.

What Happens If the Court Denies My Motion?

First, don't panic. A denial isn't a loss on the merits of your case. It just means the court believes the complaint, as written, is legally sufficient to move forward.

The case simply proceeds to the next stage: discovery. You'll be ordered to file your Answer to the complaint, usually within 14 days in federal court (though you should always check your local rules). Once your Answer is in, the litigation kicks into high gear with depositions, document requests, and interrogatories.

Dismissal With Prejudice vs. Without Prejudice

This distinction is everything. It's the difference between a temporary win and a final one.

- A dismissal without prejudice means the plaintiff gets another bite at the apple. The court is telling them, "Your complaint is deficient, go fix it and file it again." It's a setback for the plaintiff, but the lawsuit isn't over.

- A dismissal with prejudice is the knockout punch. It's a final judgment on the merits that permanently bars the plaintiff from ever bringing that same claim against your client again. This is what you're always aiming for.

Your argument should always push for this outcome. You need to explain to the court not just that the complaint is flawed, but why those flaws are incurable and can't be fixed with a simple amendment.

Ready to create polished, persuasive motions in a fraction of the time? See how Whisperit unifies dictation, drafting, and collaboration to help you move from initial thought to a court-ready filing faster than ever before. Explore the platform at https://whisperit.ai.